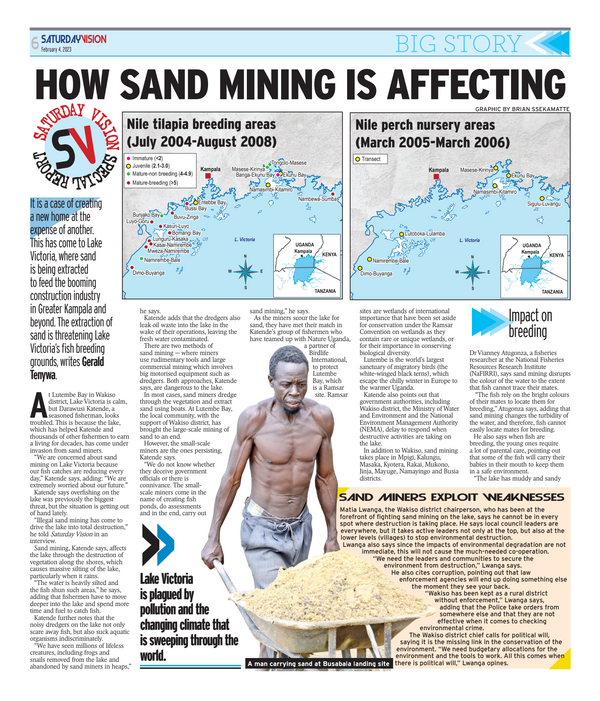

Teopista Nankinga is a weather-beaten woman who is hanging at the edge of Kampala. In the battle for survival, Nankinga has put her hands on many things including petty trade and harvesting sand in Lake Victoria at Port Bell in Kampala. “I do not like sand mining because it is risky and spoils the environment,” she says, adding that it is one of the activities that helps her to put food on the table and pay school fees for her children. The swirling sound of Lake Victoria ushered me into Port Bell. This captured the mood of the changing climate that is sweeping through the world and driving vulnerable women like Nankinga into odd activities like sand mining. While sand mining is becoming a lifeline to some local people at the grassroots, the trade is poorly regulated and Government authorities (local and central) are losing revenue. This is undermining sustainability because the environment and public infrastructure such as roads are collapsing in the wake of sand mining.

“As local Government, we do not get money from sand mining,” said Matia Lwanga, the LC Chairperson for Wakiso district. “We suffer from the impacts of sand mining because it destroys the environment.”

According to Dr. Jerome Sebadduka Lugumira, a Natural Resources Management Specialist at National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) sand is made up of silica which is a mineral. This is a form of silica known as quartz which makes glass. It is the second most common mineral in the earth crust. It comes from many different forms.

However, sand is regarded as a construction material on grounds that many people use it in construction and that it is also found in wetlands. “The challenge is that sand is widely distributed and it constitutes a material extensively used by everybody,” said Lugumira, adding that management of sand has been left to NEMA on grounds that it is found in wetlands. “There are sand deposits outside the wetlands.”

This explains how districts which are rich in sand are not making revenue from their gift. As a mineral, there would be mining leases and licenses, which would attract fees for both the local and central Governments. “The mining permits and leases are more stringent than the current regulations,” said Lugumira. “The mining cartels wanted sand to remain regulated as a construction material on grounds that it is in wetlands,” said Lugumira. The said mining regulations were put in place in the year 2000. “At the time we did not anticipate the largescale sand mining and it has been over taken by events,” said Lugumira.

Currently, there are mining guidelines which are being used to manage sand mining but they are also still in draft, according to Lugumira. The mining Act was reviewed but shifting sand and turning it into a mineral was not allowed.

Sources of sand

According to NEMA’s executive director, Dr. Barirega Akankwasah no one is authorised to mine sand from Lake Victoria and that the current said mining operations in the lake are legal. Asked why illegal sand mining is taking place on the lake, Akankwasah said that they have short comings in capacity in form of thin man power and equipment. “We have overcome the large dredgers on the lake. There was Mango tree which decommissioned and relocated to the Kenyan part of the lake.”

He added, “We still have some dredgers operating illegally on the lake. The dredgers work at night when enforcement is not alert. The problem is that NEMA does not have direct presence to monitor the lake. Apart from dredging, we want to check illegal activities including unlawful discharge of waste water in the lake.”

Lugumira said there is a lot more sand outside Lake Victoria pointing out that the water body occupied parts of Butambala, Gomba, Kalungu, Mpigi, Masaka and Kyotera before it receded to its current home today. He says that the lake dried up four times, the last time being 400,000 years ago.

NEMA has permitted companies to mine sand outside Lake Victoria. The areas of operation include; Lwera in Kalungu where three companies have permits to extract sand. There are also four other companies with permits in Mpigi, one in Butambala, one in Isingiro, one in Mayuge, one in Lugala in Mayuge and Buliisa. Others are Mukono and parts of Katosi.

The current legally-mined sand is also masking illegal sand mining from the lake as well as wetlands and drylands, according to Lugumira.

Also, unregulated mining of sand poses environmental challenges such as water pollution, hydrological risks including diversion of water bodies, flooding. As open pits of water are left behind by the unregulated sand miners, birds perching on the water come with weeds such as Kariba weed commonly referred to as Nankabirwa weed.

The current legally-mined sand is also masking illegal sand mining from the lake as well as wetlands and drylands, according to Lugumira.

Also, unregulated mining of sand poses environmental challenges such as water pollution, hydrological risks including diversion of water bodies, flooding. As open pits of water are left behind by the unregulated sand miners, birds perching on the water come with weeds such as Kariba weed commonly referred to as Nankabirwa weed.

The local hydrology in the vicinity of the mining area also goes down with water sources such as boreholes which decline and dry up. “We have started experiencing some of the impacts in some areas in areas like Lwera because of unregulated sand mining.”

The challenge with Lwera is that it coincided with the time when regulations were not up to date or up to the task. The regulations were meek to the building and construction sector, according to Lugumira. The laws had not anticipated this kind of demand. By 2016, we had 22 companies operating in Lwera. This has reduced to only four by February 2018.

The quality and quantity of sand were not known. There was no prospecting and exploration done. These were people who were associated with artisanal mining. The regulations were not keen on mining effort and size or amount of sand and the land. This is because you find somebody with 66 hectares of land all targeted for sand mining. In some cases, only 5 percent of them had sand of commercial interest. “We do not allow mining on more than four acres of land,” he said.

Also the technology which included excavators was not up to the task. “The excavators will only work where there are huge deposits of sand. This caused problems because the excavators left behind ponds at the end of the day. Upon completion, they had mined less than one percent of the entire land. The permit should be tagged to how much sand is available,” said Lugumira

Where does the sand go?

Sand from Lake Victoria and other parts of the country including Lwera ends up in construction sites within Kampala and Greater Kampala. The sand is also a big raw material in the making of dams and roads in different parts of the country, according to Lugumira. There are large amounts of sand used in the manufacture of tiles at Kapeeka tiles factory.

In some cases, the sand crosses Uganda’s border into DR Congo, Rwanda and Kenya, according to sources who preferred to remain anonymous. “The sand is exported in large containers and it is branded in a way that does not break the law,” a source told New Vision in an interview.

Who is behind sand mining cartels?

There are sand mining cartels which have co-opted local politicians including councillors and power brokers who facilitate illegal sand mining, according to sources.

Akankwasah conceded that some of the sand miners were Chinese and Nigerians helped by some Ugandans to mine sand, he insisted that no one is curtailing NEMA from enforcing the law. “I can tell you, there is no body who is above the law except a sitting President. Nobody has stopped NEMA from enforcing the law.”

How sand was formed?

The sand in Lwera was left after geological changes. The Lake Victoria was formed 400,000 years ago. At that time, the Nile was still closed and there was no river Nile. There was also no outlet at Jinja. It was after rivers namely; Katongo, Kagera, Kafu and Nkusi which used to flow into DR Congo reversed and started flowing into the Lake Victoria basin, according to Lugumira.

But the geological changes in western Uganda caused the change in the flow. Katonga has many other tributaries from Ibanda and Sembabule that contribute to its flow. The river flows into Victoria with two stream flows at Katonga bridge along Kampala-Masaka Road and Lwera.

Lake Victoria previously covered parts of the present day Lwera, Lukaya, Makoko, Lake Nabugabo and Bukakata, which have the highest quality of sand used in making of glass, according to Lugumira. The lake had many arms like Kyoga and some of which were left behind include Lake Wamala and Nabugabo. The places previously covered by Lake Victoria have a lot of sand deposits.

Way forward

As part of better management of sand, according to Lugumira, Uganda needs to undertake an inventory of sand in the country and establish its quality and quantities. This will also help to ensure that high quality sand for making glass does not end up in concrete or tiles.

“We need sand for construction of roads, dams, buildings, tiles and glass,” said Lugumira, adding that the sand should be exploited but in a sustainable manner. “We have plenty of sand outside the lake and wetlands. This means that we do not have to invade the lake for sand.” He added, “The country can exploit sand outside the lake and also benefit from fishing on the lakes.”

The country should maximize the benefits from the precious sand by establishing a glass factory within Uganda which can add value to sand by turning it into glass which can then be exported, according to Lugumira.